Vamping the Woman00:17 Nov 10 2014

Times Read: 827

Quite a fascinating article even if it`s very speculative.

URL:http://irishgothichorrorjournal.homestead.com/maria.html

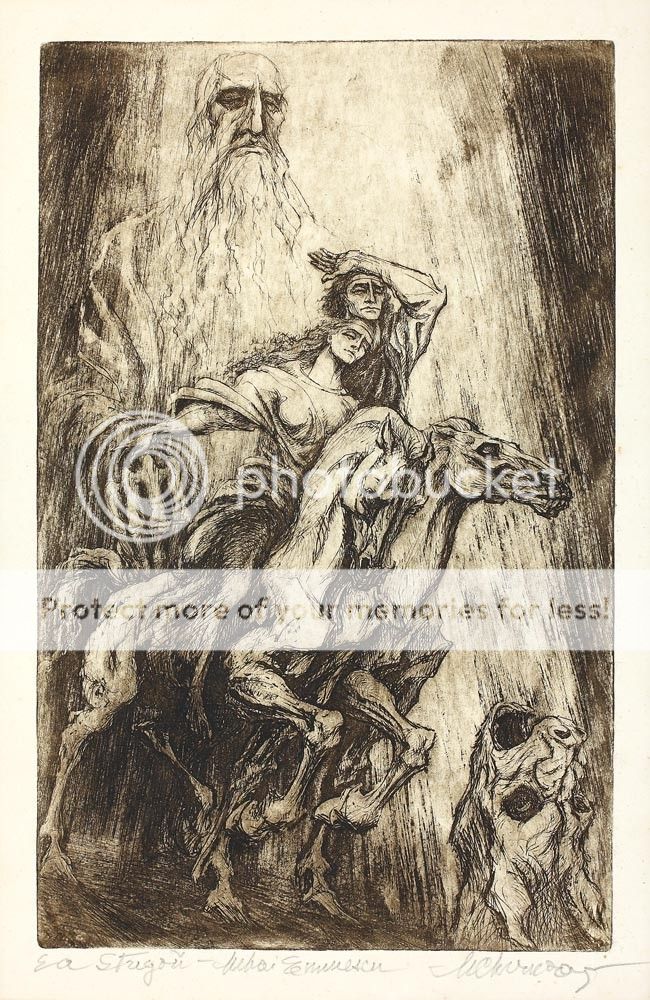

Vamping the Woman: Menstrual Pathologies in Bram Stoker’s Dracula

by Maria Parsons

MOTTO:

To destroy the vampire, suppress the menstruating woman and to look away from the Medusa, the embodiment of dangerous looking, are all responses to the masculine fear of the female.

(Marie Mulvey-Roberts)

The polarised dialectic of the idealised, perfect woman and the demonised, sexual woman has dominated dominated Western separatist ideology for centuries. In terms of the body, it reaches a significant impasse in the nineteenth century. During the Victorian period, scientific and medical advances developed alongside a resurgence of feminist activism, particularly so, from the 1860s onwards. The female activist was embodied in the concept of the ‘New Woman’. According to Lyn Pykett:

[…] the New Woman was a representation. She was a construct, ‘a condensed symbol of disorder and rebellion’ (Smith-Rosenberg), who was actively produced and reproduced in the pages of the newspaper and periodical press, as well as in novels. (2)

The New Woman not only posed a threat to the social order but also to the natural order, and was represented as ‘simultaneously non-female, unfeminine, and ultra-feminine.’(3) Incorporated into varying depictions of the New Woman was a consistent perception of her as over-sexed and unduly interested in sexual matters. Correspondingly, scientific and medical discourses began to mirror public opinion. As such, female sexuality became the locus of attention in the medical world; with the womb, the reproductive organs, and the menstrual cycle, becoming primary sites for medical inquiry and pathologising.

Prior to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the “one-sex” model dominated medical thinking in relation to the human body. For years it was commonly accepted that male and female genitals were the same. In Latin or Greek, or in the European vernaculars until around 1700, there was no separate term ‘for vagina as the tube or sheath into which its opposite, the penis fits and through which the infant is born.’(4) It was not until the late eighteenth century that the common discourse about sex and the body changed. Organs that had shared a name – ovaries and testicles – were now linguistically distinguished. The context for the articulation of two distinct sexes was, however, according to the historian Thomas Laqueur, neither a theory of knowledge nor a reflection of advances in scientific knowledge, instead, he attributes reinterpretations of the body to

The rise of Evangelical religion, Enlightenment political theory, the development of new sorts of public spaces in the eighteenth century, Lockean ideas of marriage as a contract, the cataclysmic possibilities for social change wrought by the French Revolution, post-revolutionary conservatism, post-revolutionary feminism, the factory system with its restructuring of the sexual division of labour, the rise of a free market economy in services or commodities, the birth of classes, singly or in combination – none of these things caused the making of a new sexed body. Instead, the remaking of the body is itself intrinsic to each of these developments. (5)

One of the foremost exponents in medical developments and theorizing of the female reproductive organs, particularly, menstruation organs in the nineteenth century was Dr Edward Tilt who published extensively on the subject in the latter half of the nineteenth century. His work included titles such as The Change of Life in Health and Disease, The Elements of Health, and Principles of Female Hygiene, On the Preservation of the Health of Women at the Critical Periods of Life to A Handbook of Uterine Therapeutics and of Diseases of Women. According to Tilt, regulation of the menstrual cycle was imperative to both the physical and mental health of women. As Laqueur notes

All in all, the theory of the menstrual cycle dominant from the 1840s to the early twentieth century rather neatly integrated a particular set of real discoveries into an imagined biology of incommensurability. Menstruation, with its attendant aberrations, became a uniquely and distinguishingly female process. (6)

A nineteenth century medical text by Adam Raciborski entitled Traité de la menstruation, ses rapports avec l’ovulation, la fecundation, l’hygiene de la puberté et l’age critique, son role dans les différentes maladies, ses troubles et leur traitment, (7) made the connection between menstruation and heat. Writing in an early section on heat in dogs and cats he draws an analogy between the menses and heat in women. He states ‘We will see that the turgescence – the crisis – of menstruation (l’orgasme de l’ovulation) is one of the most powerful causes of over-excitement in women.’(8) From the 1840s on, menstrual bleeding became the sign of swelling and explosion whose corresponding behavioural manifestations were aligned with sexual excitement and animals in heat. Thus, the menstruating woman was rendered as “out of control” and in need of containment.

Practical developments in obstetrics and gynaecology also contributed to the focus on the menses as the primary cause of physical and mental ill-health in women. In particular, the redevelopment of the the speculum and the curette, revolutionised gynaecological practice. Furthermore, menstrual out-flow was measured and its consistency and colour recorded in order to determine normative points of reference. This both allowed and contributed to the diagnosis and treatment of a wide ranging number of female ailments as menstrual.

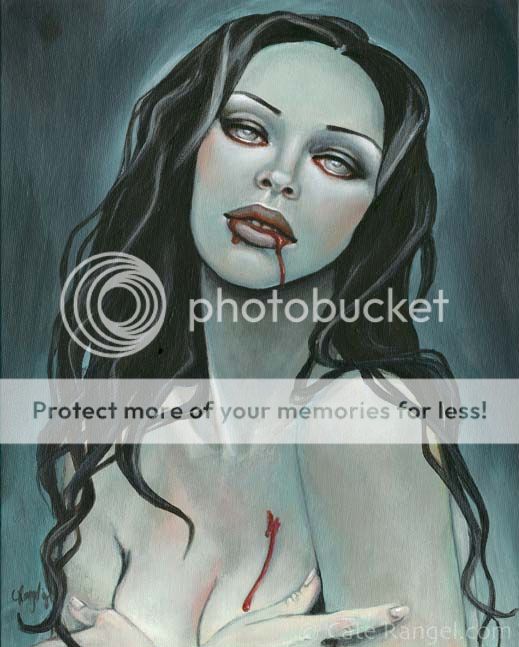

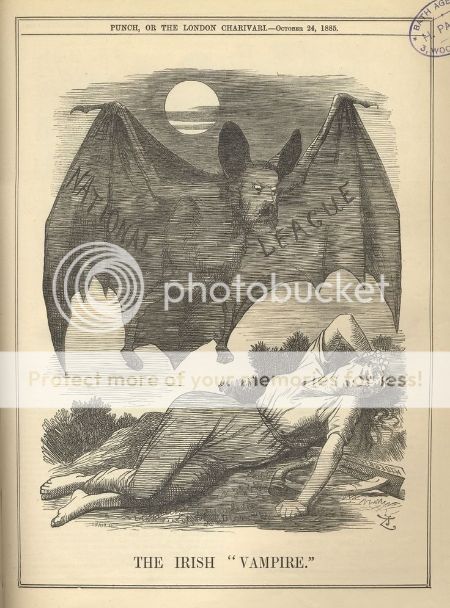

Concomitant with the medical fixation on the menstrual cycle in the Victorian period is the cultural obsession in art and literature with women and snakes and/or women and vampires. The alignment of women with snakes and vampires reinforced notions of female sexuality as lascivious and licentious. Bram Dijksta appraises this obsession as a logical leap from the myth of Eve and her temptation by the serpent in the proverbial Garden of Eden to modern womanhood in the nineteenth century. He states:

In the evil, bestial implications of her beauty, woman was not only tempted by the snake but was the snake herself. Among the terms used to describe a woman’s appearance none were more over-used during the late-nineteenth century than ‘serpentine’, ‘sinuous’, and ‘snake-like. (9)

He continues linking Lamia and late-nineteenth century feminism, claiming

The link between Lamia and the late nineteenth-century feminists, the viragoes – the wild women – would have been clear to any intellectual reasonably well versed in classical mythology, since Lamia of myth was thought to have been a bisexual, masculinized, cradle-robbing creature, and therefore to the men of the turn of the century perfectly representative of the New Woman who, in their eyes, was seeking to arrogate to herself male privileges, refused the duties of motherhood, and was intent upon destroying the heavenly harmony of feminine subordination in the family. The same was certainly true of Lilith, who, in her unwillingness to play second fiddle to Adam, was, as Rosseti’s work already indicated, widely regarded as the world’s first virago. (10)

The analogy of women and snakes as well as having obvious roots in Genesis and Classical mythology is also located in menstrual myths. In many cultures it is believed that a girl’s first menstrual bleeding occurs when a snake descends from the moon and bites her. According to Mircea Eliade, the moon-animal par-excellence has been the snake. He states:

All over the East it was believed that woman’s first sexual contact was with a snake, at puberty or during menstruation. The Komati tribe in the Mysore province of India use snakes made of stone in a rite to bring about the fertility of women. Claudius Aelianus declares that the Hebrews believed that snakes mated with unmarried girls and we also find this belief in Japan. A Persian tradition says that after the first woman had been seduced by the serpent she immediately began to menstruate. And it was said by the rabbis that menstruation was the result of Eve’s relations with the serpent in the Garden of Eden. In Abyssinia it was thought that girls were in danger of being raped by snakes until they were married. One Algerian story tells how a snake escaped when no one was looking and raped all the unmarried girls in a house … Certainly the menstrual cycle helps to explain the spread of the belief that the moon is the first mate of all women. The Papoos thought menstruation was a proof that women and girls were connected with the moon, but in their iconography (sculptures on wood) they pictured reptiles emerging from their genital organs, which confirms that snakes and the moon are identified. (11)

This connection between snakes, the moon and menstruation is further observed by Penelope Shuttle and Peter Redgrove who pose the question ‘Why snakes?’

FOR THE FULL ARTICLE see the link above.

COMMENTS

-